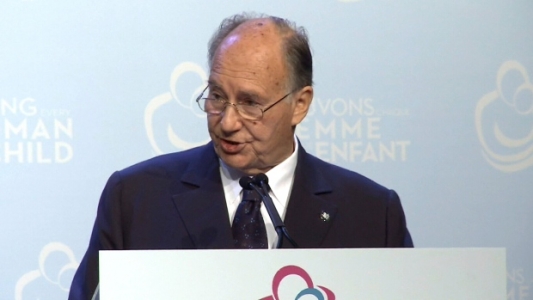

Keynote remarks made at the Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH) Summit in Toronto. 2014-05-29

Thank you Ms Brown for that kind introduction.

Bismillah-ir-Rahman-ir-Rahim

Prime Minister Harper,

President Kikwete,

Your Majesty,

Your Excellencies,

Honourable Ministers,

Distinguished Guests,

Ladies and Gentlemen:

Like you, I am here today because of my conviction that improving maternal, neonatal and child health should be one of the highest priorities on the global development agenda. I can think of no other field in which a well-directed effort can make as great or as rapid an impact.

I am here, as well, because of my enormous respect for the leadership of the Government of Canada in addressing this challenge. And I am here too, because of the strong sense of partnership which our Aga Khan Development Network has long experienced, working with Canada in this critical field.

Leadership and partnership – those are words that come quickly to mind as I salute our hosts today and as I greet these distinguished leaders and partners in this audience.

Mr Prime Minister – I recall how our partnerships were strengthened four years ago when you launched the Muskoka Initiative. It led to an important new effort in which our Network has been deeply involved in countries such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Mali.

In all of these efforts, we’ve built on our strong history of work in this field. It was 90 years ago that my late grandfather founded the Kharadhar Maternity Home in Karachi. In that same city, for the last thirty years, the Aga Khan University has worked on the cutting edge of research and education in this field – including its new specialised degree in midwifery.

One of our Aga Khan University scholars helped fashion the new series of reports on this topic that was released last week – an effort that involved more than 54 experts from 28 institutions in 17 countries. The reports tell us that right intensified steps can save the lives of an additional 3 million mothers and children annually.

To that end, our Development Network has also focused on building durable, resilient healthcare systems. One example is the not-for-profit health system by the Aga Khan Health Service in Northern Pakistan – a community-based network of facilities and health workers, including a growing number of nurse-midwives.

We have extended these approaches to other countries, including a remarkable partnership in Tanzania funded by the Canadian government and implemented in close partnership with the Tanzanian government.

Such AKDN activity now serves some two-and-a-half million people in 15 countries, with 180 health centres both in urban and rural areas, often in high-conflict zones, and embracing some of the world’s poorest and most remote populations.

Last year alone, these facilities served nearly 5 million visitors, inpatients and outpatients, with more than 40,000 newborn deliveries.

So our experience has been considerable. But what have we learned from it? Let me share a quick overview.

First, I would underline that our approaches have to be long-term. Sporadic interventions produce sporadic results, and each new burst of attention and activity must then start over again. The key to sustained progress is the creation of sustainable systems.

Second, our approaches should be community-oriented. Outside assistance is vital, but sustainable success will depend on a strong sense of local “ownership”.

The third point I would make is that our approaches should support the broad spectrum of health care. Focusing too narrowly on high-impact primary care has not worked well – improved secondary and tertiary care is also absolutely essential.

Our approaches should encourage new financial models. Donor funding will be critical, but we cannot sustain programmes that depend on continuing bursts of outside money. Let me underscore for example, the potential of local “savings groups” and micro-insurance programmes, as well as the underutilised potential for debt-financing. Also – and I think this is very, very important indeed – we have watched for many years as many developing countries, and their economies of course, have created new financial wherewithal among their people. These growing private resources can and I think should, help social progress, motivated by a developing social consciousness and by government policies that encourage tax-privileged donations to such causes.

Our approaches should also focus on reaching those who are hardest to reach. And here, new telecommunications technologies can make an enormous impact. One example has been the high-speed broadband link provided by Roshan Telecommunications, one of our Network’s companies, between our facilities in Karachi and several localities in Afghanistan and in Tajikistan. This e-medicine link can carry high-quality radiological images and lab results. It can facilitate consultations among patients, doctors and specialists at various centres. And it can contribute enormously to the effective teaching of health professionals in remote areas.

Our approaches should be comprehensive, working across the broad spectrum of social development. The problems we face have multiple causes, and single-minded, “vertical” interventions often fall short. The challenges are multi-sectoral, and they will require the effective coordination of multiple inputs. Creative collaboration must be our watchword. This is one reason for the growing importance of public-private partnerships.

These then are the points I would emphasise in looking back at our experience. I hope they might be helpful as we now move into the future, and to the renewal and re-expression of the Post Millennium Development Goals.

As we undertake the new planning process, the opportunity to exchange ideas at meetings of this sort can be enormously helpful. And potential partners must be able to talk well together if they are going to work well together.

I would hope such occasions will be characterised by candid exchange, including an acknowledgment of where we have fallen short and how we can do better. The truth is that our efforts have been insufficient and uneven. We have not met the Post Millennium Development Goals.

At the same time, we must avoid the risk of frustration that sometimes accompanies a moment of reassessment. Our challenge – as always – is a balance [between] honest realism with hopeful optimism.

And surely there are reasons to be optimistic.

In no other development field is the potential leverage for progress greater than in the field of maternal and newborn health.

I have spoken today about some of the approaches that have been part of our past work. But I thought I might close by talking about some of the results. My example comes from Afghanistan – a heartening example from a challenging environment.

The rural province of Afghan Badakhshan once had minimal infrastructure and few health-related resources. Less than a decade ago it had the highest maternity mortality ratio ever documented.

It was about that time that the Afghan government, supported by international donors, contracted with the Aga Khan Health Service to create a single non-governmental health organisation in each district and in each province. Today, the Badakhshan system alone includes nearly 400 health workers, 35 health centres, two hospitals, serving over 400,000 people. Its community midwifery school has graduated over 100 young women.

The impact has been striking. In Badakhshan in 2005, six percent of mothers died in childbirth – that is 6,000 for every 100,000 births. Just eight years later, that number was down twenty-fold – for every 100,000 live births, death has gone from 6,000 down to 300.

Meanwhile, infant mortality in Badakhshan has fallen by three quarters, from over 20 percent to less than 6 percent.

For most of the world, science has completely transformed the way life begins, and the risks associated with childbirth. But enormous gaps still exist. These gaps are not the result of fate – they are not inevitable. They can be changed, and changed dramatically.

When government and private institutions coordinate effectively in challenging a major public problem, as this example demonstrates, we can achieve substantial, genuine, quantifiable progress – and fairly rapidly.

This is the story we need to remember, and this is the sort of action we need to take as leaders and as partners in addressing one of the world’s most critical challenges.

Thank you.

- 8160 reads

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.