Note: Audio is placed below the main text, when available.

An Interview with Prince Amyn Aga Khan 2022-07-10

In an exclusive interview for The Ismaili TV, Prince Amyn shares stories from his childhood growing up with Mawlana Hazar Imam, and about their relationship with their grandfather, our beloved 48th Imam, Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah. He speaks about AKDN’s activities and some of Hazar Imam’s priorities over the past 65 years. This is a valuable opportunity to hear about Hazar Imam from someone who has been by his side for most of his life, and to gain a deeper understanding into Hazar Imam’s work across many decades.

The transcript below has been obtained from that Ismaili TV program

ZN: we are at Aiglemont. I am Zuleika Nathoo. I am a journalist normailly based in the U.s. but today I am at Aiglemont. I am in France. I have the distinct pleasure of interviewing Prince Amyn Aga Khan. Prince Amyn, thank you so much for being with us today. We are looking forward to hearing some of your memories, insights about the past, in your childhood and alsi looking ahead to the future. And this is all in commemoration of the 65th Imamat Day of our beloved Hazar Imam, So, first of all, how are you? You were travelling quite a bit, so how is everything going?

Prince Amyn: Fine. I have been travelling a lot yes. Going up and down to Portugal and elsewhere. Because of COVID, much less long distance travelling than before. So it’s been a long time since I’ve been to East Africa or Pakistan or Tajikistan or Afghanistan or what have you. But otherwise, the same life, office, house, a lot of visio work. I am not a great fan of visio personally. I think that when matters are complicated, it is often better to discuss them face to face.

ZN: Oh, visio is like virtual meetings.

Prince Amyn: Yes because you have a better feeling of reactions and a genuine dialogue than in so many of these things than you have only one face on the screen and you don’t really see how the others are reacting and it’s kind of impersonal in a funny way.

ZN: Yeah and it’s a different world because and you can’t sense the energy in other people and then you know, working technology and sometimes you hit the mute button and sometimes you haven’t and it can all add up.

Prince Amyn: But sometimes I get the feeling that difficult questions are almost religiously put off. That in fact one tends to say in fact well that’s an interesting discussion, why don’t we think about that a little more and we’ll take a discussion, talk and discuss this. It happens frequently.

ZN: That’s when you know something’s up.

Prince Amyn: I don’t know if I am right or not, but that’s the feeling I get.

ZN: So as you probably know, this interview and our conversation will be airing on Ismaili TV. And, you know, I found a quote that you had, I think, just a few years ago which I wanted to ask you about, because I thought it was quite sweet. You said to the Jamat, you know, you are all, of course Hazar Imam’s spiritual children, you are my extended family. And I wondered, you know with so many Jamati members around the world watching right now, can you describe your relationship with the Jamat around the world?

Prince Amyn: I think it’s a very personal relationship. I have sort of known the Jamat since I was three and a half years old. I mean, amongst my first memories actually are of the Jamat. And I think of the Jamat as being ina sense, part of my basic life.

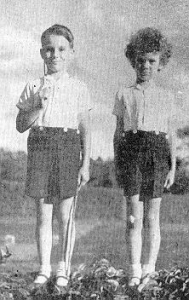

ZN: Well, you know, speaking of three and a half years old, we were hoping to travel down memory lane a little bit. If you will indulge us? We have some footage, some photos that we thought we would show you. I fyou are up for that and just sort of hear about some anectodes you might be able to share with us. So I want to start with this photo here and we’ll show them to you as they come.

1) So this is a photo of you standing next to Mowlana Hazar Imam who is reciting Eid Namaaz as a child in Kenya. And it’s such a beautifully captured moment. And I know you were young at the time, but what do you remember about that moment?

Prince Amyn: Well we had courses that my grandfather organized for us from really the day we arrived in East Africa, including prayers, including a certain amount of theory, including discussions and what have you. And this was actually for the first time that we’d been asked to lead prayers. And one of my worries was that he might forget something on the way there. And so I was behind him in case he forgot then I could whisper something at him.

ZN: That’s the best – always there you know.

Prince Amyn: Well he didn’t forget, naturally. And so it was, actually it was a very moving, a very moving moment. I was young and suddenly being in the public eye like that was unusual, unexpected. But it wasn’t necessarily frightening. It was more, impressive. I was impressed. And it was one of those moments, you know, you remember and you treasure.

ZN: You both have a very strong connection to Kenya because you spent some of your childhood there. What does it mean to you even now? What does that country mean to you?

Prince Amyn: Any number of marvelous memories. I think my second memory probably, my first memory that I could think about was flying down to East Africa in the plane. And we went through a certain amount of rather, rather shaky flying through the clouds. And I was very proud because I didn’t cry. And that was my first memory.

ZN: How old were you?

Prince Amyn: I was three and a half, something like that? My second memory was the morning after we had arrived there. I woke up early. I was always a fairly early riser and I ran downstairs to see the house, which I hadn’t really seen the night before because we had arrived late and got fed and went straight to bed. I ran down and the house had a veranda in front of it and I walked out on to the veranda and the entire lawn in front as far as the eye could see, was covered with people. It was all members of the Jamat who had come to welcome us. And I rushed back upstairs saying, “Oh! there’s people all over, all over the garden, all over the house.” Partly terrified, and I was told “no…”. And I was washed and dressed properly, what have you, and taken down to be formally introduced on the terrace to the people waiting in front. It was the first time I had ever seen a crowd. I had never seen a crowd before.

ZN: you were so little.

Prince Amyn: And I had no idea there was going to be a crowd there. (laughs)

ZN: yo just wanted to see the house.

Prince Amyn: It was a marvelous and unique experience.

ZN: And what brought you to Kenya in the first place if you don’t mind me asking?

Prince Amyn: Oh, I think it was again my grandfather who wanted us to be away from any risk of war. And so that was a good place. There was a Jamat down there and my father was basically fighting in the Middle East, largely in Syria. My mother was frequently in Cairo because of her relationship with the hospital there, Anglo-American Hospital. And we were just further down in East Africa.

ZN: Speaking of your grandfather, the next photo is a photo of Mowlana Sultan Mohammed Shah with Hazar Imam and yourself. And I wanted to show it to you because I kind of wondered, when you think about your grandfather, what do you remember the most about him? Because I think a lot of us in the Jamat know him from photos and farmans. But what was he like as a person and as a grandfather?

Prince Amyn: Well, actually the photograph is amusing of Hazar Imam and somewhat less of myself, It’s actually in a funny way, rather too stern for my grandfather.

ZN: Really?

Prince Amyn: Yes.

ZN:There’s two. There’s another one too, take a look at the other one, because I think the other one is very sweet.

Prince Amyn: Well, that’s more like it.

ZN: Really? So he was a smiler?

Prince Amyn: Yes. He had a very good sense of humour. Was a smiler. Was an excellent parent. Took great, great, great care of us at all times, and wanted to know exactly what we were doing, how school was going, how our holidays were going, what we needed, etc, etc, etc. Very, very thoughtful and very, very close. I mean, more like a parent, not like a grandparent.

ZN: Right.

Prince Amyn: So the one of him smiling, definitely. On the other hand, he would have himself go on evenings to a chair on his terrace in the South of France and he would insist on being allowed to sit there to watch the sunset. And nobody was allowed to go near him or disturb him whilst he watched the sunset and thought,

ZN: And why was that so important to him? Was it like a meditation for him?

Prince Amyn: Yes, yes, yes. And it struck me as a child again that – again there was a kind of a silent lesson there. Man with nature and man and nature both leading toward Allah. It was so clear he wanted just to be with his thoughts and with nature that one wasn’t even tempted to yell and scream, funnily enough.

ZN: So one last one. So this is a historic moment that we wanted to show you and take you back to the time that might have come with a lot of different emotions. It was when your grandfather passed away and your brother was designated as the 49th Imam. So this is a news report from when it happened. And I just want you to listen to the words, especially because it’s quite something, how it’s described. Those words like modern mind and you know …

Prince Amyn: That was partially in my grandfather’s will, don’t forget. And he felt that the world had evolved so fast and so much, that it was necessary for someone to have been brought up in this much evolved world, to take the decisions that would be necessary. And that my father wasn’t an old man by any means, but that that he was from a different time, a different perspective.

ZN: And at that moment do you remember how you felt? It just seemed like it was so momentous and you were both still so young. So do you remember how you felt at the time?

Prince Amyn: No. I think if anything, I was nervous as to how he would handle all the responsibilities which would arrive all in one go. And his ability to just not have the time and what have you to handle a whole mass of of problems and questions that would be put to him in short order. But apart from that, I wasn’t particularly nervous at all. We’d had a lot of experience, had been brought up with the Jamat since I was three and a half. So I wasn’t worried. I was just a little nervous as to whether the amount of work, the amount of decision-making wouldn’t be excessive.

ZN: I want to talk a little bit about those early years, because especially in the late fifties and early sixties, you know there was a lot of political instability festering around the world. And these were a lot of places where members of the Jamat lived. And you could probably say something like that today as well. But at the time it was probably a lot to consider and try to navigate where things might be going next. So what were some of the biggest priorities for Mowlana Hazar Imam at that time?

Prince Amyn: Well, I think to make sure that what if they did move, where they moved, they would be well received with the ability to recreate a new life both in financial terms and in terms of comfort and peacefulness and integration. So that all went hand in hand. I think it wasn’t until Idi Amin Dada that really there was a major sort of crisis shift when suddenly a large number of members of the Jamat had to leave Uganda in a hurry, taking not much with them.

ZN: Interestingly enough, it’s been fifty years now since that Ugandan crisis in 1972. And for our younger members watching, I want to explain that a little bit in case you don’t know, but that was when certain communities, Asian communities, members of the Ismaili Jamat were forced to flee. They were expelled from Uganda and faced very uncertain futures and eventually many resettled in Europe and North America and elsewhere. So I can only imagine the responsibilities that Mowlana Hazar Imam was facing at that time to make sure that people settled successfully.

Prince Amyn: Absolutely.

ZN: And so, can you tell me a little bit about that thought process, but then also your involvement with resettlement and helping Jamati members start new lives?

Prince Amyn: Well, as you say, I mean, most of the men had left in a hurry with not much. And Hazar Imam spoke with Trudeau.

ZN: Who was Prime Minister of Canada at the time

Prince Amyn: Yes

ZN: Pierre Elliott Trudeau

Prince Amyn: And got the green light for members of the Jamat to go to Canada, what have you. And I took off with Dr. Hengel, who was then working with us. And we flew together to Canada. And on the flight over, we discussed what we thought should be done to help, where the help would be necessary. And we got to Canada and I was amazed at how quickly it went. Amazed. We spoke with the Canadian banks. They were fantastic. We put together a loan programme so that the members of the Jamat there would have access to funds. We put together a sort of a bureau for information which could advise members of the Jamat as to what were the areas in the economy which were promising for new ventures and what have you, And literally, I think it took us exactly three days, maybe four, to put together the thing, It was fantastic. It was so quick. Canada already had this very pluralistic image and attitude. So it was a country where they came not as a sort of unwanted foreigners. They came as Canadians-to-be and be part and parcel of a pluralistic society in Canada.

ZN: And was that important? Identifying countries where people wouldn’t be rejected?

Prince Amyn: Yes. Well, I mean, having been rejected by Idi Amin Dada, it was very important. It was the contrary lesson, that a country, you know, that pluralism could be a working philosophy in a country, as opposed to sectarian dislikes and prejudice.

ZN: So from one crisis to another, let’s move into later decades, the late eighties and nineties and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Because among the many effects of that were on Central Asia and countries like Tajikistan in particular. So what did the conversations with Mawlana Hazar Imam sound like around that at the time? What were your main concerns and objectives?

Prince Amyn: I Think it was to find out exactly how the Jamat lived in those areas. Information, as far as I knew it, was relatively scarce and slight, both in terms of, the quantum of members of the Jamat in those countries and in terms of the lifestyle. And it really wasn’t until later, and largely through involvement in Tajikistan, in Khorog, that the full scope became apparent, I think. And, where the requirements became clearer. I think it made it easier to have contact and to actually visit and to be informed. I don’t know, but I have the feeling in the Russian period, the contact was lesser and the information less reliable.

ZN: Let’ take a break from politics. So interesting.

Prince Amyn: I am not a politician.

ZN: I love hearing about that, but I want to move to some of the institutional work and the contributions, because one of the most well-known and successful ones is obviously the Aga Khan Foundation in 1967. And when one thinks about the creation of such a large endeavor, it’s kind of hard to imagine that that was really only into ten years of Imamat at the time. Right?

Prince Amyn: Oh! Yes.

ZN: What were the, what was the vision at the time?

Prince Amyn: I think that was in many respects a reflection of why my grandfather had nominated Hazar Imam to succeed him. Hazar Imam had a vision already of institutionalising activity so that the scope could be wider, more efficient. We could have partners both in the private sector and partners in the public sector. Partners, even in the international sector. So we went in a much organizational fashion than had ever been thought of before. Working not just for the Jamat mark you, but working for the Jamat and the people who surrounded the Jamat. So we could not be accused of being sectarian or only interested in ourselves, so to speak. But already the pluralistic vision was there, that you know, the Jamat should be encouraged and helped wherever possible, but also the people around them too, so that the benefits should accrue to everybody. I think that is really one of the amazing things that Hazar Imam actually thought of all that in time as a very young man and quite, quite much earlier than most other people did. It was a very original move altogether and a very far-reaching move.

ZN: And I think also because it takes such forethought at that time to think about the interconnectedness that now we take for granted and globalization and working remotely, and you can do anything with anyone in the world, but at that time that was a foreign concept.

Prince Amyn: Yeah. It gave a kind of structure to activities which required, that needed that structure. It also allowed us to enter into partnerships that we wouldn’t necessarily have had otherwise, and to become, I can’t say, it’s presumptuous to say, an international force. But with an international presence in an organized fashion that people could understand and collaborate with and admire.

ZN: And one of the, I guess, one of the enterprises that you have been quite involved in is AKFED. And, I think, I want to explain that a little bit, because I think a lot of people automatically associate AKDN with the non-profit side of things and AKFED, which is the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development, is a for-profit enterprise that works hand-in-hand with everything else in the institutions. So can you explain, in your own words, why is it so important to have those kinds of investments as well?

Prince Amyn: Well, I mean, first of all, to improve the economic activity of the group in general. To be able to assist, if need be, and where possible, the Jamat itself in its economic activities. So those economic activities weren’t just commerce, but also reached into other areas. Another one of Hazar Imam’s big discoveries, inventions, as far as I am concerned, is Quality of Life. That to improve the quality of life, we are talking not only about living comfortably and having enough to eat. You are talking about also having a good education, having the medical advice you need and back up when you need it, and also having the cultural background so that your spirit and your and your mind and your dreams are also properly affected. And AKFED was just the economic part . And it’s been extremely useful in a sense that it went into improving conditions in rural areas, for instance. It allowed us a structured approach to helping those parts of the Jamat, maybe they were less well-off, more remote. From everything, from energy to roads, to, you know - the Foundation, of course, did a lot of that for the rural support. But AKFED was behind it. And you now have a number of members of the Jamat who have leading positions in the tourism industry.

ZN: Well the Serena Hotel chain, right, is an excellent example of AKFED.

Prince Amyn: That’s exactly why it was done, to stimulate others.

ZN: Well it’s amazing because even if you don’t, if you aren’t familiar with the development fund, the economic development fund, I think a lot of people are very familiar and have probably stayed at Serena hotels in the past. Excellent food, by the way……..

Prince Amyn: Not always.

ZN: And you know, it’s recognizable names, right, in industries that you wouldn’t necessarily associate with the non-profit sector, but that make a lot of sense.

Prince Amyn: Exactly. Job creation, training, vocational training, any number of areas that are affected suddenly by the work of AKFED. So I think it’s role, when you combine that with the Foundation or the Trust for Culture, etc., you are already doing a quality of life.

ZN: It’s a holistic approach.

Prince Amyn: That quality of life is to me a very interesting concept. And again, it was a creation of Hazar Imam’s.

ZN: Because, it isn’t what you necessarily think about as you said, it’s not just addressing basic necessities.

Prince Amyn: The human, being to be happy and fulfilled, doesn’t need only to have food on his plate. He needs more.

ZN: I feel like your heart really lies with the arts in many ways. I know you studied economics but you also studied literature. Right?

Prince Amyn: I started literature, yes. I audited courses in economis at Harvard Business School. I was accepted by B school, Law School and Grad School of Arts and Sciences. And Grad School of Arts and Sciences was considered, in my day, the most difficult grad school to get into. Which was one of the reasons I went there. I also enjoyed reading. And so it was a fairly natural thing. But, culture has always been part of my existence. My grandfather was interested in culture. He adored ballet, for instance and had some paintings and had some sculpture. My father had a collection which he sold subsequently. My mother and all of her family were deep into cultural matters as well. And so culture has always been part and parcel of what I did. All culture basically reflects the five senses we have. And all culture basically reflects the dreams and aspirations and fears that we all share. And I felt that having activities within culture was important as psychological backup to the practical backup of having enough food on your plate. As a group, the Ismailis have always had a strong cultural role. We’ve had very good painters, we have had very good poets, philosophers, you know, you name it. And I am a strong believer in culture as being one of the ways that children learn how to learn. So I thought it was important that we have that. I have pushed to have children do music from a very young age, do painting or drawing from a very young age even if they didn’t become musicians or painters. But it helps in their educational activities subsequently and makes them better students and happier and more complete people.

ZN: Because you want to teach them how to learn and not just what to learn.

Prince Amyn: Exactly. And I think also it teaches, you know, creation should be part of teaching and part of learning. And creation also shows you that learning is, can be fun and is not just strictly memory and not just a, you now, a bad mark at school because your memory has failed on that particular that day on that subject. It makes the whole thing an experience, a happy experience as opposed to being an obligation.

ZN: You have been so closely involved with the Aga Khan Museum and the Aga Kham Music Programme and a big supporter and champion of that. And I want to talk a little bit about those initiatives because I was in Toronto working as a reporter when the Aga Khan Museum opened. And I remember standing at the reflecting pool and then later inside the foyer of the building and just thinking like for the first time in Canada we have our own story to tell and we have reclaimed that narrative and our history is how we are going to tell it. So that was my feeling. You were standing outside for the first time and I am sure you go back often enough. What did you think, taking in the whole building and its beauty?

Prince Amyn: I think the building was excellent building. I am a big fan, as you probably know, of cultural dialogue. I have said this often in speeches. Man has always traveled either for commercial reasons or to conquer other territories or to find new things. And in travelling, he is always met other cultures and has imbibed those other cultures as they have imbibed his culture. So there has always been cultural dialogue and I thinks culture is by definition evolutionary. It’s a mistake to think of it as being static. And to me, the museum does exactly that. It is, in a way, a psychological or emotional counterpart to pluralism. It’s an essential part. So I was very keen and I am very keen on having the museum show exactly that. You can take a picture of Bruegal Fair, for instance, in Holland in the early years, the Middle Ages, and you put that beside a miniature of a fair in India and suddenly, you know, you see the same reactions and the human looks and what have you. These are stories that should be told, should be understood. And I like the idea of cultural dialogue, increasing cultural dialogue.

ZN: We don’t have enough of it?

Prince Amyn: Yes. I mean, to me, Canada is very strong in that area and has always been. I, of course, was personally very fortunate through my friendship with YoY o Ma and his Silk Road project which was based precisely on that assumption that the Silk Road had been a symbol of cultural dialogue.

ZN: The Ismaili Centre is in the process of being built in Houston. We have Ismaili Centres in Toronto and Portugal and many other places and I know that Hazar Imam has described those buildings as being representations. What does that mean to you?

Prince Amyn: Well, I think, they not only show what we do and who we are and how we do it. So in a sense, they represent us in that way. But they also stimulate an understanding of, for us, of what’s going on around us in that country and for the citizens of that country who aren’t Ismaili to understand what we are interested in. So we find common grounds and collaborations. So I think their role is partly ambassadorial, I guess, but it’s partly also a meeting place, a place for pluralism, a place for understanding. And our centres, after all, have classrooms. They have exhibition halls now, they have social halls, they have landscaping in which we show, you know, the mixture of so-called Oriental landscaping with Western. So I think they play an important role.

ZN: How important is that right now, having a place where people can try to come together?

Prince Amyn: They can discuss and you can do lectures. You can do everything from poetry readings in public to lectures and other things. So they become a centre of intellectual discourse as well.

ZN: As we move towards the end of this lovely conversation, I want to ask you to kind of take a step back and look at the most important principles that have informed the work of Hazar Imam over the last 65 years. What would they be in your mind if you have to narrow them down?

Prince Amyn: Well, I think assisting the Jamat in every possible, particularly improving the quality of life of those parts of the Jamat which are less fortunate. As I said, I think pluralism has been a message, a big message. I think, quality of life has been a big message too. That life is a complex thing and has to be treated in all its complexities. So, I think, the discovery of the requirements of the members of the Jamat, the grassroots, accuracy of those, of the information on the grassroots has been important. So I think there have been a lot of very basic, very basic lessons and activities. The partnerships, you know, we now work with all sorts of people that we never worked with before. There are so many areas I think that are new and fundamental. And I think have modified the way we are, the way we act. We are no longer, I mean, we are international.

ZN: Well, you have been by Mawlana Hazar Imam’s side since childhood. So, you know, not to mention the 65 years of Imamat. So, you said, that your grandfather took a moment every every day to meditate on life in front of the sunset. In those quiet moments for yourself, what do you think about when you try to reflect on what’s been done since you were children and since this whole journey began?

Prince Amyn: Well, I try to be relatively pragmatic on these things. I try to, I always try to think of what is new and could be done in a new fashion. Either a new activity or an existing activity in a new fashion. And I am eager to, personally, to improve things, improve the quality of what we do. So, taking stock, seeing what can be done better, doing it better, seeing what are the things that are not are not being done that should be done, etc. I think are more important and I have always thought like that. In that sense I am a very positive person. I am always looking for how, what can be done that is new? What can be done that’s better? And I think that has been really, I would say a guiding, prejudice, but a guiding motivation behind what has been done these past 60 odd years.

ZN: Do you have anything else that you want to add or say, yo know, a message to Hazar Imam on his, on Imamat Day or anything else you want to message?

Prince Amyn: Message is, you know, my love and every conceivable wish, what have you. Hazar Imam and I are, we are nine months minus one day.

ZN: I know, so close in age.

Prince Amyn: I was very premature. And, so really, we’ve been brought up as twins almost. And we have very twin-like reactions, it’s curious. The most typical of those, funnily enough, was when I was working in the UN and it was my third year at the UN and Hazar Imam had started the Sardinian venture and I had the feeling from what I was hearing that it was a difficult enterprise altogether and on my way back from – I used to walk from the UN up to my house in New York – on my way back I thought I am going to call him tonight and see if he, you know, if he wouldn’t like me to come back and work with him, as we used to do in the past. I get to the house, the telephone rings. And who is it? It’s Hazar Imam. He said, have you ever, ever thought of coming back and working with me the way we used to do in the past?

ZN: And did you say, no I haven’t?

Prince Amyn: I said I was going to call you and make exactly that suggestion. As coincidences go, this must be a very, a very unique coincidence frankly. So, that’s how it happened.

ZN: Well thank you. That was really, really lovely.

- 1892 reads

Interview

An Interview with Prince Amyn Aga Khan 2022-07-10

Posted August 31st, 2022 by librarian-hdIn an exclusive interview for The Ismaili TV, Prince Amyn shares stories from his childhood growing up with Mawlana Hazar Imam, and about their relationship with their grandfather, our beloved 48th Imam, Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah. He speaks about AKDN’s activities and some of Hazar Imam’s priorities over the past 65 years. This is a valuable opportunity to hear about Hazar Imam from someone who has been by his side for most of his life, and to gain a deeper understanding into Hazar Imam’s work across many decades.

- Read more

- 1083 reads

All Related Articles

| Interview |  | An Interview with Prince Amyn Aga Khan 2022-07-10 | ismaili tv |

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.