Interview with His Highness the Aga Khan, with The Globe and Mail. 2002-01-30

GM: Your Highness, thank you very much for seeing us, we really do appreciate it. These opportunities come few and far between.

AK: Well maybe they didn't mention this, but I've had a long-standing regard and respect for the Globe and Mail. You may not know it, but you actually helped me create what is East Africa's biggest media group.

GM: Really!? How is that?

AK: A long, long time ago, and it was a time when the British were withdrawing from East Africa and I thought it was important to have a media group that reflected the new societies in East Africa. My role was not the media entrepreneur, but it seemed to be a national need and I put together with the help of others a consortium of newspapers that were highly regarded. And the Globe and Mail was one of them.

GM: What year would that have been?

AK: Mid sixties, something like that. Mid sixties.

GM: Your community in that part of the world was mostly in Uganda at that time?

AK: No, no, no, no. Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Zanzibar, Mozambique, Rwanda, Burundi, Belgian Congo I think it was then, South Africa, Madagascar, all down the East African coast. Things have changed since then.

GM: We'll begin with some of our questions. We do very much want to get your views on a few of the issues. In fact we first attempted to contact your office last September, not long after the tragic events of the 11th, because we wanted to hear your thoughts not on the events so much, but particularly on the manner in which Islam was being portrayed.

AK: Right.

GM: Now as a leader within the Islamic world, within one aspect of it, but still sort of influential in that role, I wonder if perhaps we could begin by just asking you to reflect on how you think Islam has been treated by the Western world since September 11th.

AK: Well I think the reflection in the media in the Western world of what is called ‘Islam' is perhaps a reflection of a misnomer. Because Islam is the name of a faith, it's not the name of a country or a geographic area or a number of countries, and therefore what goes under the word Islam really should be considered a faith. And one needs to separate I think the understanding of Muslim populations and their diversities from the notion of the faith, see what I mean? It's as if I said ‘what is Christianity doing with regard to Northern Ireland?' You would say to me ‘what's Christianity got to do with the Protestant/Catholic relations in Northern Ireland?' You see, that's not a reflection of Christianity. What I'm trying to explain is that there is no such thing as a truthful pool of people who are all of the same profile, practice the same interpretations, that live in the same way, speak the same language, live in the same economies. The Islamic world is very, very diversified. So I think the first point I would say is that it's important to make the difference between the faith of Islam and the peoples of Islam. They are not the same thing because the peoples of Islam practice different interpretations in different circumstances. And that diversity within what we call the ‘Umma' - that is the totality of the Muslim community if you want -- that diversity wasn't reflected on the 11th of September. It took quite a long time for the media to enter into the issue to understand that what happened on the 11th of September was not an expression of the faith of Islam - it was an expression of a certain group who had certain interpretations of their own and which certainly were not validated by the totalities of the Muslim world. I think it's important for you to accept the premise that there is enormous morality in the Islamic world. African Islam, Asian Islam, Central Asian Islam, Arab Islam, even within the Arab world there are these enormous differences. So I am very uncomfortable with the notion that what happened on the 11th of September is in any way a portrayal of the totality of the Muslim people of the world, I assure you.

GM: Do you think that Muslim leaders do enough, do they do an adequate job of explaining Islam to the West?

AK: I think they do as much as they can, taking into account the absence of the understanding Islam in Western general knowledge. It is a, from a Muslim point of view, it is a very difficult issue to deal with when you think back and you look at what is considered general knowledge in the Western world and you say within the general knowledge of the Western world what does it know about the Islamic world? Is anything taught in secondary education? Does anybody know the names of the first philosophers or scientists, the great theologians? Do they even know the names of the great civilizations? And I have to say civilizations because the history of Islam is a history of civilizations, not just one. And it is very, very difficult for Muslim leaders to articulate positions against such a vacuum in knowledge. I was a student in North America so I recollect very well what used to be called ‘general education' courses and you have them in Canada in universities. These were imposed courses that were designed to educate people on, if you want, global matters. There was a total absence of anything to do with the Islamic world. It was a blind spot. That blind spot causes Muslim leaders to react to a vacuum in knowledge. And it's often difficult for us to understand the basis of your questions because we assume that there is a certain amount of basic information that you understand. I think one of the most striking examples is what was the knowledge in the West about Islam, and I'm talking about general knowledge, I'm not talking about academic knowledge, before the Iranian revolution. The word ‘Shia' was unknown. The fact that Islam has the visions within like Christianity, and Judaism, that was unknown. So there has been for a long, long time, an enormous vacuum of general knowledge. What is part of the Islamic world simply is not part of general culture in the Western world. Now I have to tell you very frankly, it is the source of immense concern to many of us because we suffer from that. We are responding to situations where there is no equality in a dialogue because there's a vacuum of knowledge on one side and there's a response to that vacuum of knowledge on the other side. So I have to tell you very frankly I think the response has taken a long time to understand what went on. First of all, if you look at the situation, a lot of people didn't ask themselves, is it Islam the faith, or is it political forces within the Islamic world? Second question, is it political forces within the totality of Islam, or only a part of Islam? Third question, what are the motivations of those forces? So you know, it took some time before the Western media started putting the picture together in the complex nature that it is. I'm not willing to blame the Western media, but I'm saying that it is the absence of basic knowledge which has caused the Western media to look at the Islamic world as though there were such a thing as one Islamic world, and that the events of the 11th of September represent that one world.

GM: Can you take one of those few questions that you think the media should have asked themselves, perhaps the last one, what is the motivation of those who have carried out these acts? Can you offer us your insight into that?

AK: Well, I think that what we are seeing is probably, and I wouldn't say it's the only reason, but I think we're seeing from part of the Islamic world a sense of profound injustice which has been part of our history for many, many decades. And because there is this sense of profound injustice, which has never been corrected, perhaps never recognized, that part of the Islamic world has reacted. And has said ‘why are we being treated unjustly?' And worse, ‘why is this injustice specific to one part of our world?' In other words, you look at other areas of the world, now I'm purely talking about the Middle East, but you look at other parts of the world, the Western world has been generally equitable, but there is a profound sense of inequity with regard to the Middle East. What happens? What happens is that when you have these areas of perceived injustice, whether it's the Middle East, whether it's the Philippines, whether it's Kashmir, whether it's even Northern Ireland, whether it's Sri Lanka, what happens over time is that these areas of injustice or perceived injustice or perhaps both, end up overcoming internationalists. This sickness, if you want, goes outside of the frontiers of the area of concern. Sri Lanka, you know what happened. The Philippines you can see it today. And so I think that the lesson from this, one of the lessons, is that these international situations of crisis cannot be allowed to continue year after year after year because in the end, they create an international security issue. So that's the way I would interpret this, I think that's really the basis of it.

GM: What are the injustices that you see in the Islamic world that they might particularly be reacting against?

AK: I think certainly the Palestinian situation is one which is perceived by the Arab world and many people in the Islamic world look upon as an injustice. I think the Kashmir situation is another one where there is a sense of incorrectitude in the way events have evolved since the partition of India into India and Pakistan. If you take the case of Mindanao -- the situation started if I can recollect, somewhere around the mid-sixties -- this was a community of people who felt that they were isolated, abandoned, left aside from the development process in this country. So it's these situations, and it's not only in the Islamic world, that's the point I want to make. I don't want, or I'd like to avoid the feeling that this is specific to the Islamic world. It's much more specific to ethnic differences, demographic differences, economic inequity, political situations which remain unresolved.

GM: Many similar conflicts exist, I think you were suggesting, in non-Muslim parts of the world, Sri Lanka being an obvious one, and these have not been globalized in a violent form. They've been debated globally. Why is it that these particular grievances that you raised have been globalized or externalized in a violent manner?

AK: Would you say that the assassination of an Indian Prime Minister is not an internationalization?

GM: Well that was a specific revenge attack for a specific action.

AK: I'm saying that you say they're not internationalized. I'm saying they are internationalized, but they don't necessarily manifest themselves in the sort of thing we saw on the 11th of September. Northern Ireland, they did it to become internationalized. So the point I'm making is that this process of exteriorization outside the direct area of conflict is one which is I think one has to be honest about. Now clearly in the case of the Middle East, there is a wider spectrum of people who feel emotionally engaged in this situation, but the fact that they internationalize it is a reality.

GM: You've spoken in the past, well before September the 11th, about some of the difficulties or challenges of Muslim nations to secularize. Is that still a great challenge for those countries, and do you foresee it happening in the near term?

AK: I can't give you a single answer to that, and the reason is that the history of these nations is very different one from the other. If you were to take the Central Asian republics, their relationship to the faith of Islam, relationship to democratic processes is very different from what happens in other parts of the world. But I think the more over-riding issue is the issue of theocracy versus secular state, and I think that at this point in time, the vast majority of countries within the Muslim world have recognized the difficulty of a theocratic state, and these difficulties are due to many different forces in these countries. But also, the pluralism within Islam. Because if you create a theocratic state, automatically you are saying there must be an interpretation which is the state interpretation of the faith. So that alone is a very, very difficult question to ask. And you can see, I don't have to name the countries, you can see what happens when these internal stresses occur in states which would present themselves as theocratic states. So I think the answer is most of them are going towards a secular state, but I would want to avoid the notion of a secular state without faith. What we are talking about are states that want to have modern forms of government but where the ethics of Islam remain the premises on which civil society is built. And I think that's where we see this -- to me very exciting -- effort to maintain the ethics of Islam, but in a modern state. And I think when we're talking about the ethics of Islam, it's easier to have civil society institutions built on the ethics of the faith, than a theocratic state in the full form.

GM: In the Muslim world, could you name a state that you think has got it just about right?

AK: I would find that inappropriate. What I can tell you is that the (inaudible) search process in many Muslim countries today is a solid, well-predicated process. But I can't tell you what the outcomes are yet there because I don't think that would be equitable in the sense that all the states that I can think of have gone through or are going through processes of transition, and I cannot say that those processes of transition have reached their final goal, because as far as I'm aware, they actually haven't -- because they're in a process of change.

GM: There does seem to be within the Islamic world a great tension between those individuals and groups of individuals who seek the theocratic answer -- they carry a banner and say ‘this is the way' -- and others who say, 'No, no, we must avoid that and maintain in many cases an oppressive if secular government in charge of the state.'

AK: You're right.

GM: Algeria ???

AK: You're right. You're right. There are those internal tensions within Muslim communities, but not only in Muslim communities. There are other countries where those tensions exist within Christianity, between the Orthodox interpretations and the Catholic interpretations - it's part of the internal, I'm looking for the right word, fabric of faith relations in pluralist societies. That's a fact.

GM: Can you explain, though, I've spent some time in Islamic countries and there is one problem, particularly among the young, educated people - they tend to turn to Islam and the theocratic solution in great numbers right now. What is the appeal?

AK: I ask myself how great those numbers are. I would say that when they're put to the political test, they're actually often less numerous than they appear to be. A case in point would be Pakistan. So I just want to make the point that I'm not sure in my own conviction that the numbers are as great as they might perceive, or be perceived. They are very vocal, they're very visible, they're well organized, they have a point of view. Whether that point of view represents the majority of the population of a given country, I would find very difficult to say because I'm not certain of that. But I think within those groups that you're talking about, there are a number of things which are of concern to me. I think the first thing is the nature of governance. The use in many, many countries of their own views on the nature of governance, the competence of governance, etc. So the nature of governance is an issue. I think the nature of the economy is another issue. Young people who are educated have an entitlement to have decent employment, and in a number of countries, they don't find that. There is no systematic relationship between the state of progress of the economies, and the number of people who are being educated. So there's frustration. I think there are sometimes some moral issues vis-à-vis the West where there are attitudes in the West where some of our people, and I'm talking now about youth in the Muslim world, not just the Islamic community, ask themselves is there a dividing line between freedom and licence? And if there is a dividing line between freedom and licence, which is a highly important ethical question to every person, where is it? Is it where the West has situated that divide, or is it where we would like to see it? So I think there's a multiplicity of questions which the Islamic people are asking - I think they ask themselves about the freedom of their countries when they find that their economies are constrained because somebody says you are going to go into a period of recession because your government's been spending too much, that creates frustration. So I think there's a number of forces that play on news that we have to accept.

GM: Do you think the masses that you're speaking of understand the West? We spoke earlier about the misconception of Islam.

AK: Yes I think they understand the West, whether they're empathetic with all Western values is a question I would have to say no to. They are not empathetic to all Western values.

GM: Which values?

AK: I would think that things like economic independence they would find it very difficult to find their countries in some way dependent on international financial institutions that make or break the cost of the kilo of rice. I mean, we're talking about very basic issues. Think of the food, the food rebellions that you had when the IMF amongst others said you've got to correct your economy. People couldn't buy their food. You know, how can you expect young people not to react? That is so basic to human rights. So those are things that I think are felt, that people feel very bitter about. I think at times representation of their countries, their people, their faith were just disgusting. That is sensitive. When there is a wilful, or misinformed interpretation of Islam, that is unpleasant. When there are maybe political processes which are encouraged but have failed. Democracy is a wonderful concept, but it's not failsafe. It doesn't work in every country in every time, it doesn't work.

GM: Has the West been too aggressive in pushing democracy on countries that may not have the same political traditions as we do?

AK: Again, I'm not sure if the issue of democracy per se. To me the issue is how do governments change in developing countries, what are the processes. That's where I think the democratic system has caused problems. It has caused instability. Democracy with fifty, sixty, seventy national parties is not a very solid formula for stable government. So you know, I think that if you look at it from the point of view of the Third World, you can see that there are wonderful concepts but they do need to be worked through very, very carefully. Because if they fail, the concept is rejected.

GM: This week the President in the United States, in the State of the Union Address, mentioned what he called an "Axis of Evil." There's North Korea, there's Iran, and there's Iraq: Two of those three are Muslim nations. How did you feel when you heard that?

AK: I find it difficult to pass a moral judgement on all Iran or all Iraq. I will not do that. I have to tell you very frankly. I will not stigmatize a whole population as being evil. Whether they are Muslim, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, I will not do it. It is, in my view, a very serious issue. I can't do that. If he wants to say that the people in government are responsible for things that he doesn't like, that's his prerogative. But don't stigmatize a whole country.

GM: Do you think he's done that?

AK: Well that's what I interpret your statement. That's what you tell me.

GM: Certainly those were his words...

AK: If that's the way...

GM: He was careful to focus on the leadership of Iran.

AK: Yes, but you see what I mean, can you imagine how sensitive that is for every Iranian living in the world? To say the President of the most powerful country in the world today has stigmatized me as an evil country?

GM: He has also drawn the world in half between those who are good and those who are evil. Do you agree with that analysis, and what effect do you think that is having on the progress of the world?

AK: I'm not sure the divide is quite that clear, frankly. I think that what we're talking about is the introduction of a further extension into countries of the developing world of what I would call a ‘state of law.' I think it is the issue of law and the way law is applied in these countries which is the central issue. And there, there are all sorts of different tones, if you want, you can't say all the countries of the developing world or the Muslim world are either law-abiding countries, or lawless countries. I interpret it in those terms, rather than ‘you are with us' or ‘you are not with us.'

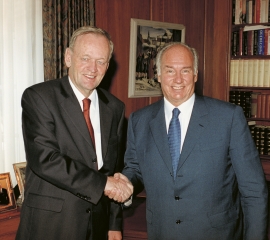

GM: Beyond these individual statements of President Bush, how do you think that he and Prime Minister Chrétien -- you've met him here in Ottawa --have portrayed the Islamic world since the crisis of September 11th?

AK: I think they've been very good, because I think they have recognized that you cannot tar the faith of Islam with the 11th of September. And therefore, that you have got to make careful, careful analysis of what really happened and then put the blame on those who are responsible. But don't tar a billion people. Turn it the other way around - when people were killed by the IRA in London, what would you say if the Muslim world had got up and said the whole of the Catholic world or the whole of Christianity is morally or directly involved in this? You would say to us Muslim leaders and Muslim people, ‘you are crazy'. You don't know what you're talking about. I think.

GM: Is this what the Prime Minister wanted to ask you today?

AK: No, we had discussions on things like Afghanistan, on Central Asia, on Canada's role in this crisis, these were the issues we discussed.

GM: What do you think countries like Canada should be doing in Afghanistan and where do you see Afghanistan's future going?

AK: Well, let me then maybe dive in at the deep end, okay? Let me dive in because I want to say to you something which to me is profoundly important with regard to the developing world, which I know, and we're talking essentially about Africa, and Asia. Canada is today the most successful pluralist society on the face of our world. Without any doubt in my mind. You have created the perfect pluralist society where minorities, generally speaking, are welcome, they feel comfortable, they assimilate the Canadian psyche, they are allowed to move forward within civil society in an equitable manner, their children are educated. So Canada has succeeded in putting together a form of pluralist society which has been remarkably successful. I'm not the one who's making a judgement. Look at the international evaluation of Canada as a country and the way it functions. So what I'm saying is that Canada has succeeded in an area where the developing world has one of its greatest needs - how do you build a pluralist civil society in the developing world. Look at Africa. Look at Asia. Look at most of these countries which you and I observe every day. What are one of the characteristics - the inability of different groups to live together in peace, in a constructive environment to build civil society. And whether it's the tribal conflicts of Africa, whether it's the religious conflicts of Asia, whether it's the political conflicts in various countries, so many of them come back to the basic premise of people who cannot live together because the psyche, the notion, the acceptance, the legitimacy of pluralist human society has not established itself in the public domain. And I think Canada is really a country which has a remarkable opportunity to share its experience. I'm not suggesting that you go around saying ‘we've got it right and you guys have got it wrong', what I'm suggesting is we need to learn how you've done it. We need to know, and the best people to tell us are going to be people from our own backgrounds who are living in Canada. They're the ones who I think are going to be the best articulators of this. But, so that's the question, the answer to the question it's rather long, I'm sorry, but what can Canada do - that is something unique to Canada. It is an amazing, global, human asset.

GM: How would you see it being carried out?

AK: That's been part of my discussions here, and I'm approaching it with other people. I think it's so much a part of Canadian life that it's very dispersed in civil society, it's not just one phenomenon, one area of human endeavour. So I think the first question I would ask myself is how does it happen? Because it doesn't only happen, it's a process. It's not something which, you know, starts there and finishes tomorrow, it's an ongoing process. And clearly Canadian leadership and Canadian people have had to respond to challenges all the time, this doesn't, it's not a course which is free of obstacles, but they've been addressed. So I think the first question would be how do we put it all together? What has enabled this to happen? Is it in political life? Is it in judicial life? Is it in economic life? Is it in religious life? What are the forces of civil society which coming together created this pluralist society that functions? Once, and I'm not Canadian, but once that is better understood, just a sharing of the knowledge could be an extraordinary gift to many of the countries I know.

GM: Now you've been coming here for many years, you must have some observations on what does make it work here.

AK: My sense is that Canada has attached, for historic reasons, necessary value to pluralism because the country was born in a pluralist context. In language, in faith, etc. with people who were here of course before even the Canadians staked claim to it. So, you started with a pluralist context, within a pluralist context. You lived in a bilingual environment, and bilingualism became important. So you started with the requirements to be a pluralist society, but you've made a success out of it. Extrapolate that to the developing world. Isn't that true also of much of the developing world? Countries with different faiths, different languages, different ethnic backgrounds, they have many of the same starting premises as Canada had. And what is fascinating to us, observers from the developing world if you want, is how you've done it. I feel that if we could learn from that and share it, we would be creating a fantastic thrust toward pluralist civil society. And I'm not talking about politics, you know politicians tend to view this as a political process - yes, part of it is political of course, but it's not just a political process.

GM: How do you think the interim government in Afghanistan in this regard is setting the stage for adding pluralism to Afghanistan?

AK: I met with Hamid Karzai in London some time ago, then two days ago in Washington, I've met with Dr. Abdullah Abdullah many, many times, the Foreign Minister, and I think these senior Afghans are deeply conscious of the fractures and the fissures within Afghani society. They are well aware that rebuilding Afghanistan is going to need time, it's going to need finding equitable solutions to development opportunities, development problems. And I know because Chairman Karzai actually said it to me, that Canada is a country where the pluralism of society and the successful management of that pluralism is something which he and others in Afghanistan will be looking at.

GM: When did he say that?

AK: Two days ago.

GM: Really? Did he study Canada?

AK: Well we discussed it together. Obviously we discussed it. Because anyone who is engaged in Afghanistan as I am is going to be asking the same questions. How do you rebuild the society in Afghanistan?

GM: So he's taking the right steps in your opinion?

AK: He's taking the best steps he can take at the moment. I mean clearly, problem number one is security. Clearly. Problem number two is keeping the people fed. Problem number three is rebuilding what can be rebuilt in a quick enough time so that this slide into collapse which we've been observing for so long starts getting reversed. So we're talking about short term steps and all agencies that I know that are working in Afghanistan -- the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, United Nations Development Program -- we're all working on the same premise: there is a short term and we have to look for immediate results because frankly, the environment plus the base information we all have is not good enough to let us envisage long-term programs.

GM: But there are external actors who want to disrupt that process, and it's often said of Canada that if we had external actors intervening in our affairs, say propping up Quebec separatist movements, that our pluralism may not look so good, or our success may not have been so great.

AK: That happens!

GM: Well, at a more aggressive...

AK: Am I right? ‘Vive le Quebec libre!'

GM: What has to be done about these external players who continue to meddle not just in Afghanistan, but in many of the cases you've referred to?

AK: You know, Afghanistan really was a situation where many people felt they had a legitimate right to meddle, let's be quite frank about it. What you call ‘meddling' wasn't meddling in the sense that you and I would be using the word. These were countries whose ethnic minorities were on the other side of the Afghan conflict and they felt both a direct and a moral responsibility for what happened to the Uzbeks, what happened to the Tajiks, what happened to the Hazaras - so you talk about meddling on the other hand, it's very difficult not to be concerned with the future of these communities. I think the question now is different: Is there a consensus around the vision of the future of Afghanistan? And that is the key question that the coalition has to work on, the interim government has to work on, everybody involved in Afghanistan has to work on. That's a vision which is not yet fully formed in my view. And as it's not yet formed, people are saying to themselves, how can I position myself so that I can control that the forming of this vision comes out the way I would like it to come out. I don't think it is an intent to meddle, as you said, indefinitely in the future of Afghanistan. I don't believe that because when all is said and done, everybody in that area has a strong interest to see a stable, well-governed Afghanistan. This is a law-abiding state, where terrorist activities are not encouraged, are not exported, where the drug business does not destroy lives and damage thousands of people in the neighbouring countries. So there is a consensus I think of wanting a stable well-governed Afghanistan.

GM: With all due respect, that was also said in 1992.

AK: Well...

GM: And some of the parties seemed to have an interest in destabilizing Afghanistan?

AK: Yes, maybe I wouldn't call it destabilizing, I would call it gaining control. It's different. Remember that these parties in 1992 had fought a common enemy, but they did not have a common vision of the future of their own countries. They had very, very different opinions on what the future of Afghanistan should be. Between 1992 and 2002, a number of those component groups of the 1992 situation, a number of those groups have fallen by the wayside, or have been marginalized, or they have been told stay out of the rebuilding of Afghanistan. Don't destabilize the situation. And one of the problems the West had, I think, was probably insufficient observation of how the United Front evolved between 1992 and 2002. United Front in 2000, 2001, 2002 had nothing to do with 1992. They were not common in any way. So I think it's unfair to tar the situation today with the image of what happened in 1992.

GM: Do you have a fear that the United States may overstay its welcome in Afghanistan?

AK: You know it's difficult for me to predict what President Bush is going to do. What I would want to say is that the future of Afghanistan, to be an acceptable future -- probably to the Afghans, even to the neighbours -- is that it's got to be an independent, self-governing state. It is not, I can't find a different word in English, but it's not the lackey of somebody else. Because there are so many different interests around Afghanistan, if the country is not a self-governing, independent country, building its own future, and it has stable friendly relations with its neighbours, it's going to fall out of line. So I think that's the key question and my sense is that that is understood.

GM: Does Hamid Karzai seem to have this concern as well that they not be seen as ‘lackeys,' to use your words?

AK: No, I don't think Chairman Karzai is worried about it. Because he has been talking to a large number of different people, Tony Blair and the British, he's been talking to the Russians, he's been talking to the Saudis, he has had the wisdom to talk to all the parties who have an interest in Afghanistan, so I don't think he's worried about that at the present time.

GM: While we've had our eyes on Afghanistan in the last while, quite a number of American troops have been entering the Philippines. I understand these forces will be dispatched to the south, to an area of Mindanao. Are you worried about an escalation of the situation?

AK: I am not in any way a specialist in the Philippines, and I know it much less well than I would know Afghanistan or Central Asia. I think the key question here is what we talked about originally, which is the state of law, and I think that where we're talking about law in independent states and there are activities in those states which are clearly outside the framework of international law, then in that case, they must find solutions if they don't want these situations to continue indefinitely. Now clearly I would prefer to see a political and economic solution. Rightly or wrongly, and I have to tell you this is my own direct experience, many, many of these situations can be avoided and addressed in good time. Many of them. And I really assure you that this is the case. These pockets of extreme poverty, of frustration, of fear of some of these minorities, can be addressed by a direct, focused program to bring them back into civil society so that they understand that they are not isolated and thrust outside the context of national mainstream. And it is amazing how much can be done if you will go in with economic support, social services, dialogue, bringing communities together, focusing on hope in the future rather than looking backwards in despair. That looking backwards in despair is probably one of the most divisive forces that you will ever find in Third World countries.

GM: Do you think the West though has learned this lesson and committed enough resources? Let's just look at the case of Afghanistan, and the pledging conference in Tokyo: Is that sort of commitment enough to address these problems?

AK: Let me go backwards. The World Bank has changed massively between 1960 and 2002. Today the World Bank is concentrating on the factors of human development, and it is identifying areas where human development is desperate. That wasn't done in the sixties. So the bank, and I'm just giving this as one example, the bank is saying ‘I understand that these situations of despair are very, very volatile environments'. So the answer to your question is, an institution like the bank definitely has moved in that direction. Tokyo is a different issue to me, you know I may be wrong, but Tokyo is not a situation of quantity of money, it's the ability to deliver programs in Afghanistan. There what have you got? You've got a country whose intelligentsia has been eliminated - either destroyed or left the country. And to rebuild in a short time without the harnessing of that intelligentsia, is going to be very, very problematic. So I think that one of the conditions for rebuilding is going to be harnessing that intelligentsia from outside of Afghanistan so that teachers, doctors, economists, bankers, come back into the country to help rebuild civil society because civil society as you or I know it has been destroyed. So the answer to your question is I think Tokyo, yes, it was a good meeting, but now it's the implementation which is going to be the tough question that we all have to answer.

GM: Your organization has many years of experience in helping communities develop in the Northern Areas of Pakistan, terrain very similar of course to that of Afghanistan. Can the experience of the Northern Areas be tried in Afghanistan?

AK: I think I can give you a few answers. I think the first one would be that you cannot rehabilitate communities by single input actions. That's the first thing I would say. If you go in there with a rural support program but you don't go in there with a simultaneous education program, or a health care program, or a micro-credit program, it's not going to do the job. So, the first answer is what I would call the multiplicity of inputs into these environments. Because you can't always tell at a given time which one of those inputs is going to be the driving force for the development process so you need the multiple inputs first. I think the second thing is you need to get in the rural environments -- I don't like the word but it's in use in my organization, so I've got to learn from my own organizations -- it's a thing called the social organizer. And the social organizer is the man or the woman or the team who go in and explain what village processes are to people who have never thought of it as a village. Instead of thinking of themselves as an individual community, individual family, here is a village. How do you create that notion that the whole village can move in one direction or another if they will work together? And of course the third one is micro-infrastructure.

GM: I spent some time in the Northern Areas, in Hunza, and saw how the work there is quite extraordinary and I was always struck at how successful it was and yet similar efforts down on the plains didn't work so well.

AK: Yes, you're right.

GM: Without referring to specific governments, why is it that you're able to have success in one geographic region and not in another?

AK: There's probably a number of answers, but one single one which is the biggest condition is the land ownership pattern. If the land ownership pattern is highly fractured as it is in the Northern Areas, then you need a village structure to operate on the consolidated land context. If you're talking about areas such as Sindh, you have enormous land holdings, owned by one family, and with paid labour. So the sorts of things we can do in the Northern Areas, you couldn't do in a different land ownership pattern. I think that's the basic premise.

GM: In a way it as eco-cultural -- economic and cultural?

AK: It's actually perceived economic return. In the context of the Northern Areas, the perceived economic return is the increase in disposable income that the individual or the family gets from this joint exercise. If it's in the land holding situation, the same family has no control over the term that that family gets if it increases the productivity or increases the budget because it's paid labour. And that's why I just don't think that the Northern Area's programs are applicable to other areas of Pakistan with enormous land holding and transient labour.

GM: Would they then be applicable to Afghanistan?

AK: I believe so.

GM: More so than, say, on the plains.

AK: Yes.

GM: I know our time is running short, I'd like to get your thoughts on some broader development themes and how your thinking has changed over the last decade towards free enterprise and democracy which were such dominant issues ten years ago. The results have been mixed. Has your own thinking changed in the past decade?

AK: Well, yes, of course. I have become convinced that the only real course for change is people. You can throw money or technology at given situations, but they don't cause the form of permanent change that development represents in my mind. The development process is enabling people to make permanent changes, to make choices of their own and that means building civil society and it means placing the pillars of civil society under the control of good leadership and enabling environments. That construction of civil society is very important. And it depends on the country, but if I give you the example of the Central Asian Republics, I've often felt how difficult it must be for people who for fifty years were told you have to work exclusively for a centralized government. What you produce is not yours. It belongs to the central government. The central government determines what you will grow and when you will grow it and where you will grow it. It determines what you will be paid for your product. And it goes further. It says if you cheat on the process, you will be punished because what you produce is not yours. It belongs to the collectivity. Then a few years later somebody comes in and says all that doesn't stand up anymore. Now you work for yourself. What you produce is yours. Your income is at your disposal. You grow what you want where you want. You grow as much as you want, you work as hard or as little as you want. The whole of your economic environment is 180 degrees in the opposite direction. Think of the psychological problems of adapting to that change. It's very, very difficult. And people are not accustomed to making their own decisions in that sort of an environment because they have lived for 50 years, their decisions would have been made elsewhere. So in that sort of a situation, you say, ‘What have I learned?' I have learned that in that sort of environment, all of us are at the bottom of a learning curve. All of us . . . There's another factor which is extraordinary. It's that we're dealing with populations that are highly sophisticated. Even though they're very, very remote. They are bi-lingual. They have all had access to good education. They can all read and write. We're not dealing with human society which is incapacitated by lack of education. The Soviet system gave these people extensive education. So, you can't make the comparison between Tajikistan and Pakistan. You just can't do it. So the answer to the question is humility.

GM: Are you still as firmly committed to the idea of free enterprise as you were a decade ago?

AK: Yes. Within certain ethical principles, of course, but yes, I think that when you look at the development process, its strength is based on the people's will to work for themselves. That's clear. And we've seen that.

GM: We haven't talked about gender which is too important an issue to address in a few minutes. But there's been a great debate about gender in Muslim countries, post-September 11th. Where do you see the debate going in these countries?

AK: I find it very difficult to validate the concept, for example, that Islam says a woman cannot be educated. Or that Islam says that a woman cannot work. I think what Islam says is that men and women have to live in a dignified manner in civil society. I think Islam says there is a tendency for the male half of society to dominate and at times become overbearing. You in the Western world have laws, you recognize that risk in society and you recognize it by laws in work, by laws in equity of employment and things of that sort, so I don't think there's a big difference there - it is a structural issue in society. What I'm saying is that I think in the Islamic world, there will be an acceptance that women must function and try to function in civil society in a proper, overt manner. But that does not mean that that line I told you about between freedom and licence can be crossed. I think that's where the difference lies . . . So I certainly see a change occurring, I think it'll take time. There are risks, you know. There are risks in forcing the issue. Educated women in societies which are not accustomed to educated women within their midst can reject educated women. If they reject educated women, those educated women find their destiny outside of those societies. So I think it's a little bit foolhardy to say let's simply say women automatically have to be educated and everything is going to fall into place - that's not true. That's not true. There are social limits . . . In our own community I think women have demonstrated, including here in Canada, that they can be very, very well respected people who have very high roles and that's what I would hope. But I think that the problem for you in the West and for us in the Islamic world is this structural issue of the female society versus the male society.

GM: Do you think the West has a greater problem in coping with that notion of divided societies?

AK: I think the West is recognizing it. And I think the West is more and more concerned about how you manage that problem. I sense that there is legislation coming in which is being thought of to protect that issue from going into what I would call ‘licence'. It's quite interesting - I sense a reversal from the positions that were taken ten, fifteen years ago. I may be wrong because, you know, I can't judge.

GM: What legislation are you speaking of?

AK: Well I think that if you take the Internet, there are serious questions about the ethics of the use of the Internet. I may be wrong. But I think ethical questions have been asked. I think ethical questions are being asked about the way people behave in the work environment. I think ethical questions are being asked about people - how they behave in the armed forces. So, where the male and female in society work together or have joint responsibility, there are questions for all of us. It's not a question just for Islam, it's a question for all of us. That's the way I look at it. I may be wrong.

GM: Thank you very much.

AK: Well I don't know whether this has been of any use to you, but . . .

GM: It's been wonderful, I'm particularly grateful for the length of time you spent on Islam, and I think we've taken away a little bit of new knowledge.

AK: Well I hope in looking at what's happening around us you'll get a sense of it not being quite as black and white as it's being presented, quite as simplistic.

GM: Can I just ask you one small question: Your trip to Canada has been very quiet, there wasn't much of a public announcement here. There was a very small press release yesterday, but it was very quiet. Is that how you always plan trips?

AK: That's how I prefer things. I think when you look at the nature of work, you're more effective in the complex environments that I work in if you are discreet, and what I'm concerned about is that the programs and projects should be understood, not what I personally am doing with them. If there is a successful institution or a successful program and it can be replicated, that's the sort of thing I like to see articulated. (Here, the Aga Khan is asked to speak about his network's relationship with the Canadian International Development Agency.)

AK: We've had some wonderful success stories in programs with CIDA, and I simply wanted to put that on the table because sometimes in Canada, from what I am told, questions are asked about what's working and what sort of successes there are. The rural support program in Pakistan has worked with us for I don't know how many years, 17 years . . . The second one is the Aga Khan University, where we started with a school of nursing, with McMaster, we went to higher education for women. This school of nursing is now carrying out work in East Africa, it's been at work helping Afghanistan. So I simply wanted to say these are the sorts of things that I should have shared with you because these are joint programs where we are benefiting from Canadian know-how, particularly in the field of nursing, for example. And we're able to take this Canadian knowledge, build on it, create institutional capacity, and then get the institutional capacity moved to other parts of the world. So in that sense, when we talk about programs that are successful, choose if you want to mention that these are two of the programs that I have in my mind which I value very, very, very highly. Very highly. I mean I have to tell you the capacity of rural support programs to impact people's lives in these high mountain environments in Asia is fantastic. And now of course I'm going to move that into the University of Central Asia so that it becomes part of an academic process that will cover 22 million people. This university will affect a population of 22 million people who live in the high mountain areas of central Asia.

GM: That would be Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tajikistan.

AK: Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and ourselves, plus the right to any other country to join us, but it's a university that's come into existence through an international treaty process, and the reason for that, that I needed a political guarantee that this would be a self-governing university. That we would not get pressures from people to do this or to do that. And it is an international treaty, the parliaments have agreed with it, so I think this is a remarkable thing that a program put together nearly 17 years ago, with Canadian help, is now moving into a structured presence which can impact so many people because clearly the University of Central Asia is going to be teaching partially from the knowledge-bases it's gained from (inaudible). That you were asking about developments - that is an area of very, very great success, I think. Fascinating to me.

GM: Is that region attracting enough donor resources? It often doesn't get much attention.

AK: No, you're right. Process of change is (inaudible). That's been recognized since the 11th, since the Afghan crisis and there are corrective processes in place now. But you're right. You're right. Now I think there's another issue in (inaudible) which is frankly that people underestimated the time it would take to train socialist societies into productive use. So you know, I think it's a moot point as to whether things could remain constant.

GM: Would it take decades?

AK: Yes. Certainly in my mind, 10 or 15 years. Because amongst other things, the knowledge of things we discussed. You're asking people to think differently and you're telling me what was criminal last year is desirable and remunerated and morally right this year. It's really, from a human point of view it's typical. I really at times ask myself what is the psychological turmoil that these people go through?

GM: I guess that's what universities are for.

- 14994 reads

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.