The Age Interview, Geoffry Barker, ‘Aga Khan: Enigma of East and West’ Melbourne, Australia 1979-10-31

Interviewer: Geoffrey Barker in Aiglemont

From the Sunday Nation, Nairobi, which republished the interview

His Highness the Aga Khan recently gave a candid interview to the Melbourne newspaper, “The Age,” on a variety of topical issues. He is due to visit the Australian city at the end of October for the climax of the spring racing carnival and to be guest speaker at a “Racehorse of the Year” presentation jointly sponsored by the newspaper and the VRC [Victoria Racing Club]. He was interviewed By Geoffrey Barker.

From The Age, Melbourne, as published by the Sunday Nation

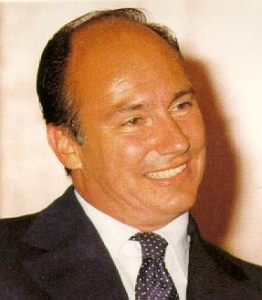

His Highness the Aga Khan moves enigmatically between the spiritual East and the material West. He is an [sic] exotic, infinitely adaptable but inherently different. He stands alone, unique.

To 15 million Shia Ismaili Muslims in 25 African, Asian and Middle Eastern countries, the Aga Khan is the 49th Imam, the descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. He is the possessor of the Nur, the light, and his word on the interpretation of the Qur’an is absolute and infallible. He is the spiritual leader whose commercial, philanthropic and social welfare activities seek to ease the desperate poverty in which they and their countrymen often live.

The Aga Khan, now 42, became Imam in 1957 on the death of Aga Khan III. He is, according to his associates, a workaholic who is driven by a high sense of the obligations and privileges of his exalted spiritual and temporal position.

In the 22 years of his Imamat the Aga Khan has vastly expanded his activities both in the Third World and the West. In the Third World, he has done so against a background of war, revolution and political instability. To his associates his achievements are a tribute to his diplomacy and persistence; to outsiders they might equally seem a tribute to the power of his money and highly professional organisation.

Given his position, wealth and power, the Aga Khan is a gentle, even modest, man. He has none of the casual arrogance that frequently afflicts the rich and noble of Europe. He is quietly spoken, self-contained and quite unhurried. In a 1 1/2 hour interview the Aga Khan spoke freely about his religious affairs and his attitude towards events in the Muslim world.

[Below is an edited, by The Age, transcript of the interview.]

Geoffrey Barker: Do you regard yourself as an Eastern or a Western man?

His Highness the Aga Khan: I would hope as a world citizen in the sense that I have no problems with the East or West. Really, I think that one’s dealing in my position with humanity. You see humanity, you are aware of humanity. You know the problems are different but the basic issues are the same.

GB: I’ve been told that you seem a different personality in the East. Are you aware of any change in your mental attitude when you are in the East?

AK: No. I think there is certainly more empathy with the East emotionally, culturally, historically. That is natural. I was brought up in the West but I don’t always understand the West.

GB: What don’t you understand?

AK: Some attitudes.

GB: Such as?

AK: Social attitudes which I find difficult. I think they are transitional….

GB: Could you give me an example of some of these attitudes?

AK: Well, I think that freedom of … maybe some of the freedoms seem to bordering on license at times. I think also in terms of certain freedoms of comment, certain freedoms of attitude towards other people which to me are areas of concern. I think for example at times the media, some of the media, are involved in things which I disapprove of. I think they are damaging to society. They may have their justification … but I think at times they are disruptive.

GB: Do you think you pay a penalty for the sort of publicity which surrounded your grandfather and father?

AK: I think there may well be hangover. I think I could have addressed myself to that problem if it had been an issue of concern within the overall scheme of things …

GB: What’s the Imamat worth?

AK: No. It’s confidential. I think if you asked the Pope he would give you the same answer.

GB: What are you worth personally.

AK: I wouldn’t be able to tell you that … I might know it but I wouldn’t tell you … I am not concerned with wealth. I am concerned with what wealth is doing. I have absolutely no business interest in the Western world other than the two you know about … Costa Smeralda and horses. I have no intention of extending those in the Western world and I have every intention of expanding extensively in the developing world.

GB: Westerners see an incongruity in your dual roles as a religious leader and international businessman. Do you think you are an incongruous religious leader?

AK: The incongruity exists through your tradition, through your experience, the Augustinian interpretation, if one can call it that, of Christianity…. In Islam there is no reason why a dichotomy should exist. Every Muslim no matter what sect he comes from, will tell you Islam is a way of life. If you read the Qur’an you will find that a very substantial part of Islam and Islam’s teaching has to do with the individual’s behaviour in society in totally secular matters — how you behave in your relations with other people in society, in your business transaction, in your family, in your friends.

GB: It is often suggested that your affluent lifestyle is very different from that of most Ismailis who live mostly in the poverty of the Third World. Do you think that is a fair comment?

…

AK: I think that affluence is perhaps the wrong terminology. I do not seek to do things, in fact I have stayed away from things which did not seem to me to be good sense, where it was affluence for the sake of affluence. I’ll give you an example. I have a private aircraft, but that aircraft today is flying between 450 and 600 hours a year. You take 600 hours of time — that translates into approximately two months of working days.

I cannot afford, nor can people who work in my organisation, to eliminate two months of working time … if you have to run an organisation in as diverse areas as I do there are certain things you’ve got to do to be efficient.

When you talk about extremely poor people, of course there are poor people throughout the developing world and there will be poor people for years and years. I think they would ask whether the Imamat as an institution was helping them as best as it could and I think it would be true to say that the Imamat is assisting them.

GB: How do you exercise your religious authority?

AK: If I have a decision to give it will be a decision which I have discussed extensively with people in my own community. We will look at other people’s attitudes to the same problem and the decision will be given by the Imam as a decision for the future.

GB: You make no claim to be divine. But do you believe you are divinely guided?

AK: Divinity is a very difficult thing to define in verbal terminology. Therefore I would object to anything which uses the term divine in my context. I have inherited an office and I seek to fulfil that office to the best of my judgement. To tell you what inspires that judgement … I don’t think any individual can answer that question. You seek within yourself that which tells you what is the right thing to do.

GB: Do you see yourself as a reforming or conservative Imam?

AK: I think that is terminology which just does not apply in the sense that the essentials are the essentials and have remained the essentials for centuries. So I think reform as such doesn’t exist. Conservatism could exist in secular terms, not in religious terms.

GB: How do you account for the rise of fundamentalist Muslim attitudes in the Third World over the recent years?

AK: This is, in a sense, a set of historical forces. Most of these countries were governed by foreigners in recent history, people of an alien culture, an alien faith, of an alien race. When independence was given to these countries it took some time for the identity of the people of that country to come back to the forefront again.

That’s what’s happening now and the interesting thing that I find is the way in which this identity is coming forward is not the same from one country to another … but I think it is in a sense a resurgence of the basic identity of these countries which is coming forward in history — not a revival of fundamentalism as such.

GB: Westerners are often appalled by the literal implementation of savage Qur’anic laws which permit, for example, public beheading of adulterers, the chopping off of hands and flogging for breach of alcohol prohibition. How would you as Imam defend these laws? Do you insist on their implementation among the Ismailis Muslims?

AK: You must be careful not to refer to Islamic law. There is no such thing as “Islamic law”. There are four basic schools of Islamic law in the Sunni Muslim world, there are several schools of Islamic law in the Shia Muslim world.

AK: You must be careful not to refer to Islamic law. There is no such thing as “Islamic law”. There are four basic schools of Islamic law in the Sunni Muslim world, there are several schools of Islamic law in the Shia Muslim world. Our attitude is simply that codes change and that what is important is the purpose behind the code.

I must say that in certain areas of the Muslim world there is a very rigid application … I am not at all saying that today the Ismaili world would encourage mutilation or flagellation or things like that … Flagellation, beheading, mutilation, these sort of things, may be a totally temporary aspect which is put forward as maybe a justification at a time of crisis.

I think you will find that generally speaking the Muslim world will not be going in that direction.

GB: Are you concerned by the revolution in Iran and its aftermath?

AK: Yes, very definitely. I am concerned about the interpretation of Islam which is being given. I think many, many Muslim leaders are concerned about that … I am not convinced as Imam of the Ismaili community that that interpretation is the right one. Now seen from within Iran, there may be a different attitude. I am saying today that law and order in the 20th century can probably be achieved without the application of law as it is interpreted there.

GB: What prospect do you see of Ismailis going back to Uganda now that Amin has gone?

AK: I don’t think the thousands [of] Ismailis who went to Canada and who went to the UK will return to Uganda. I, generally speaking, have advised families who have been through a very, very deep crisis not to expose themselves to that again in the same generation because that is highly destructive.

GB: Does it concern you that Amin, a Muslim who persecuted Muslims, is now being given sanctuary by Colonel Gaddafi who is also a Muslim?

.

AK: Absolutely. There may be political reasons for doing it but there is nothing in Islam which would encourage one man to protect another man if that other man has persecuted people of his own faith. That is totally wrong from a theological point of view. In turning against certain Muslims just because they were of a different race, Amin committed a very, very fundamental breach of Islamic brotherhood.

GB: Do you think the OPEC countries are acting in the best interests of the developing world and the West by pushing oil prices so hard?

AK: Within OPEC there has to be a willingness to accept that there is a worldwide responsibility on oil producers … The developing world comes to the West and says: “Give us 2 per cent of your GNP as assistance.” That is, I think, ethically an acceptable request, but that request has to be within the context of what the Western world can do reasonably, rationally, without disrupting its own economies.

The second thing is that the impact of the oil crisis is infinitely more damaging on the developing world than on the Western world. That is something which is perhaps not yet sufficiently recognised. The impact of the increase in oil on the Indian economy, the Pakistan [sic] economy, the Bangladesh [sic] economy and the Indonesian economy is catastrophic, absolutely catastrophic, and these countries which have enormous populations…. We can seek assistance from the developed world quite rightly. I have nothing against that. But it’s got to be done within a universal attitude and not a parochial me against you.

GB: How do you assess the chances for Middle East peace in the light of the Egyptian-Israeli agreement and the response of the rest of the Arab world?

AK: This is a very political question and I find it difficult to deal in political terms as a matter of principle … My hope is that the issue of the Palestinian people can be resolved … While the position is unresolved I don’t think you can really consider that peace to be anything more than a paper peace.

GB: Has any writer or thinker been outstandingly influential in forming your political or commercial attitudes?

.

AK: I have taken, I think, a pragmatic attitude because I think that in the developing world that is the only attitude that can be taken. What we are talking about really is the maximisation of resources … the most effective way of assisting the growth of these countries and of their economies and therefore of getting that benefit back to the people who reside in those countries. If one political system is working and is giving good results, the idea of disrupting it for an “ism” is not an applicable concept to me.

GB: In a 1976 speech you stressed heavily the role of private initiative in developing economies. Do you believe that private initiative alone or overwhelmingly is capable of meeting the needs of the developing world?

AK: I think private initiative is absolutely fundamental, absolutely fundamental. You are talking about countries with numbers of people which are just incomparable with the Western world. You have got to mobilise these people to look to improve their lot because it is physically, and just in sheer numbers, impossible for a government to be the motivator, the exclusive motivator … the issue of standards is fundamental. That’s where private initiative can really contribute in a substantial way.

GB: Do you believe that high standards are causally linked with private initiative?

AK: Yes. I think there is no doubt that private initiative has an attitude towards standards which governments find difficult to apply because governments, particularly in developing countries, are caught between serving numbers and producing quality. That qualitative issue is a very, very fundamental issue.

GB: You have said the IPS companies invest to fulfil social needs as much as to make profits. Would you invest to fulfil a social need if you could see a likelihood of nationalisation?

AK: We would very definitely do that. We would take every reasonable measure to protect ourselves against the risk of nationalisation, but we would still go ahead if we felt it was necessary for the future of the people in the area … The funny thing is that generally speaking there is a recognition in time, even if you go through the process of nationalisation, that it may not have been the right decision … There are a number of countries which try to apply a social philosophy and have found after 10, 15, 20 years, that the philosophy has really so damaged the initiative of the citizens of the country that the ultimate result has been less good than the original purpose … and there is a liberalisation.

GB: What have been your best and worst business decisions, and why?

AK: Do you know something very strange? I am not really interested in business, and that really is the truth. I am interested in what initiative will produce results not in terms of money. The things that have given me the greatest happiness in the material field would have been improvement of management throughout the banking and industrial institutions and the opening of these institutions to the nation rather than the community.

GB: How much money did IPS make last year?

AK: I have no idea. There is no consolidated balance sheet for the simple reason that these are national institutions.

GB: What is the source of IPS funds?

AK: The Imamat essentially plus members of the community. The general approach I take is that the Imamat — i.e. funds which I will control — are invested as seed funding. If we believe in the project, we will invite the community to join. We will tell them absolutely openly and frankly what the forecast is. Obviously we won’t dump a thoroughly bad operation. Sometimes I have had to go into bad operations to try to salvage a thing which appeared crazy.

“The ‘sheer joy’ of a good horse”

[NOTE: Accompanying the interview transcript, The Age also featured the article below with additional quotes not published in the interview.]

It’s a game of chess with a nature … you spend a long, long time watching families develop and strengthen. You watch others disappear and weaken. You try to establish the sires that are becoming the dominant sires in the period you are living through.

And then you produce a foal from a mating you have worked out and it goes into training … and you know it’s what you wanted. You know why you did it.

The Aga Khan is sitting in the Aiglemont headquarters of his international racing and bloodstock empire talking about the form of horses. He plainly delights in the heady sensation of leading a big winner past the applause of the crowd — he also derives profound aesthetic pleasure from his role in the creation of a champion.

Maybe over a 20-year period, (he says), the possibilities of logic and reason being right are 50.0001 per cent … the breeding is fascinating. The management of horses in training is fascinating. The sheer joy of having a good horse, of seeing foals and mares at stud, is something which is totally different from any other activities I have.

Outside, on five acres of rolling grass and woodland, enclosed behind high. stone fences and electrically controlled gates, are the Aga Khan’s stables, probably the most modern stables in the world….

The Aga Khan refuses to disclose the value of his racing empire, but he told me that the break-up value of the establishment would show a profit. He said he would operate for three to four years at a loss before a good horse would emerge and give him a profit.

Since my grandfather died, my attitude has been essentially to keep the strongest assets I have in my control. I have reinvested to capital growth. I will not sell a semi-classic filly. I will put her back to stud.

The Aga Khan said the sale of his record-breaking two-year-old Blushing Groom to American interests had enabled him to purchase the stock from which Top Ville came and to pay partly for the Aiglemont training centre. Top Ville, he added, would pay for the Boussac purchase and complete paying for the training centre….

It is perhaps a measure of the Agha Khan’s [sic] love of horses that he refuses to bet on them.

If a big breeder and race horse owner were to start running his stables according to the betting, (he said), you would never see the end of it. It would disrupt all values — it would disrupt all consistency. I just don’t want to run the thing that way. If I have a good horse, I want to run him in the race which is right for him.

The Aga Khan seems interested in producing horses that are fast over short distances, rather than stayers. But he remains concerned to protect two-year-olds from premature damage.

You breed good horses with speed, (he says). When that happens, it means more emphasis is going to go on to two-year-olds. We are going to have to breed two-year-olds that are fast. My own attitude is that two-year-olds by April will tell you whether or not they are precocious and fast … If he dominates of his own capacity, without being bullied, that is a two-year-old you can run. But to take a two-year-old that doesn’t dominate and push him in order to start racing in April, over a five furlong race, we just wouldn’t do that. You would damage your horses.

The Aga Khan came to horses late in life. He bad no knowledge of or interest in horses until he inherited the stock left by his grandfather and father in 1957 when he became Imam of the Ismaili Muslims. It took him six months to decide to keep the horses. He decided to do so, he said, because he did not want to see the end of a four-generation tradition in his family and because he decided he would-have the time to devote to it….

During the racing season, he said he tried to see all races which were “important for the future of racing“, especially maiden races and transitional races from maiden races to semi-classic and classic races.

Although he has not previously visited Australia, the Aga Khan and his family have had a long association with Australian jockeys in Europe. Bill Williamson Bill Pyers, Neville Selwood and George Moore have all ridden for him. On the wall of his stable office there is an antique,print of the horse West Australian (“Bred 1850 by, Melbourne out of Mowering. Trained by John Scott. Ridden by Frank Butler. Winner 200 guineas and St. Leger 1853”).

(The Aga Khan said the Australian jockeys he knew were) exceptional … excellent horsemen with, I would say, a very good sense of the race. As a family we have been very, very fortunate with Australian jockeys.

The party accompanying him on his visit to Australia will include the manager of his stud at Ballymany in Ireland, Mr. Ghislain Drion, and the executive secretary of his French studs, Madame R. O’Bin. But, the Aga Khan said, he would not be making purchases in Australia. The expansion of his activities over the past three to four years now demanded consolidation.

SOURCES

The Age, Melbourne, Australia, 14 July 1979, pp 4

[Text verified and/or corrected from this source by NanoWisdoms]

Sunday Nation, Nairobi, Kenya, 12 August, 1979, pp 13

[Text verified and/or corrected from this source by NanoWisdoms]

- 10243 reads