Yo-Yo Ma: The road runs smooth as silk - YO-YO MA: THE ROAD RUN SMOOTH AS SILK - 2003-05-26

Yo-Yo Ma was fascinated by the wealth of music along what was once the Silk Road. So the cellist conceived a plan to weave together the multifarious threads, as he explains to Michael Church

Geographically, we're just up the road from Afghanistan; musically, we're both nowhere and everywhere; and politically, we're somewhere rather interesting, given the violent return of the age-old fear of a clash of civilisations. A posse of young Americans - plus musicians from Central Asia - are serenading the political establishment in Tajikistan, in an ornate oriental hall. Tajik musicians reply in their traditional musical language; the visiting ensemble counters with orchestral Bach, souped up with the tabla; there follows an increasingly sparky musical exchange, after which the leader of the visitors is granted honorary Tajikhood, and presented with the finest local lute that money can buy.

What is the purpose of this encounter, and why is it happening in this dirt-poor land, still traumatised by a savage civil war? Not so long ago, life here got so bad that many Tajiks sought refuge in the Taliban's Afghanistan: the Soviet yoke seemed bliss in retrospect. For a bunch of (relatively) rich Americans to ride in, show off, and accept gifts, might be thought a shade risky in these edgy times, but their leader's answer, when he has got his breath back, engages head-on with present discontents.

Yo-Yo Ma is a blend of Chinese, French and American cultures, and, five years ago, conceived a cross-cultural project of majestic symmetry and scope: a Silk Road for our times. The original medieval road stretched from the Mediterranean to Japan, and was based on trade in consumer goods: it was also the conduit for the secrets of gunpowder, mathematics and glass. 'I regard that as the internet of antiquity,' says Ma. He'd noted the way that objects cropped up in surprising places: East African stones set into the back of a lute found in the ancient Japanese capital of Nara; a medieval plectrum decorated with an elephant, a Persian man, and a Chinese landscape. Researching the ancestry of his own instrument, the cello, he began to make stylistic connections between the Persian spike-fiddle, the Kazakh kobuz, the Tuvan horse-head fiddle, and the Chinese erhu, all of which are played in a similar way. It seemed a good idea, he says, to open up a new Silk Road, which followed the same geography, but whose trade was in music.

Thus germinated a project designed to highlight those parts of the world that - until September 11 - had dropped off the West's mental map. Nobody now needs telling about the importance of Central Asia, but shockingly few people - apart from the US military and Clare Short - can tell the Central Asian 'Stans' apart. These countries have always been desperate: arbitrarily carved out of Russian Turkestan in the Twenties, they became dumping-grounds for the Soviet state's problems, with Kazakhs serving as guinea pigs for nuclear tests. Kazakhstan may be oil-rich now, but, like its neighbours, it's riddled with poverty and corruption, and that means with anger, too. Ma had planned to start the tour in Tashkent, until the State Department warned that it was unsafe. Yet 500 years ago, these states were the hub of a great civilisation, whose architecture and music were its crowning glories. 'We want to give something back,' says Ma, 'to the people who in the past have given us so much.'

He accordingly enlisted the support of Central Asia's most discreetly powerful player, in the form of the Aga Khan. This hereditary leader of the Ismaili branch of Islam believes that today's burning issue is less a clash of civilisations than what he terms the 'clash of ignorances'. It may come as a surprise, to those who think of this elusive 67-year-old and his family in terms of yachts, palaces and racehorses, to learn the scope of their humanitarian activities - largely through the UN - over the past 50 years. A champion of tolerant pluralism, he has initiated scores of medical, environmental and architectural projects in the undeveloped world, but Islam is his guiding thread.

And while helping to rebuild Kabul, he has also decided to pour money and manpower into Yo-Yo Ma's scheme. Thanks to the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), Central Asia's musical heritage may be reborn, and, through it, the Stans' emerging nationhood may get a boost. When you remember that Kazakhstan alone is the same size as the whole of Western Europe, you realise what is at stake: to these countries' mineral wealth you must add great strategic importance, both militarily and as the abode of Sunni Islam.

But that rebirth is problematic, because the identity of the infant is in doubt. The Soviets spent time Europeanising the Stans' local music - putting nomad lutenists together to create vast orchestras - and in Kazakhstan, we were serenaded by the still-flourishing results. The Kazakh government proudly regards that as 'traditional', but Ma's musicological advisers emphatically don't. In Tajikistan, we heard the nomad lute grotesquely accompanied by grand piano: chalk and cheese, so no again.

No one should demand that 'traditional' music stand still - it must develop or die - but some local forms are so 'foreign' that it's hard to know what to do with them. At a government reception in Kyrgyzstan, Yo-Yo had just received honorary citizenship (again) and made his acceptance speech in perfect Kyrgyz (the consummate diplomat), when a gnarled and imposing figure - very evidently just down from the mountains - was ushered into the hall. The figure took a series of deep breaths, rolled his eyes until all we could see were the whites, and launched into a trance-like recitation laced with groans, hisses, shouts, and rhythmical chants. This was Kyrgyzstan's own national epic, which is said to last three weeks if recited in its entirety, but even this 10-minute excerpt was haunting. 'When I recite it, I'm dwelling with God,' explained the bard, through an interpreter, afterwards. And for once, Yo-Yo Ma was lost for words. 'Amazing. We've got to find a way to work with it,' he muttered, shaking his head.

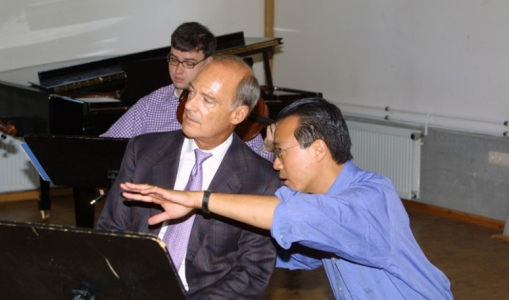

Being on the road for a week with this indefatigable cellist - leading his troupe from country to country, playing morning, noon and night, and still outpacing people half his age in daily sessions in the gym - one is forced to admire what he has already achieved with this visionary scheme. He has surrounded himself with musicians who are all virtuosi in their own right, and he has commissioned works from Asian composers who meld instruments and styles from East and West. His young American percussionists set up an exhilarating dialogue with his Indian drummers; his Iranian spike-fiddler Kayhan Kalhor - darling of this year's Radio 3 world music awards - galvanises the New York violinists. And with Chinese pipa-player Wu Man, with Azerbaijani praise-singer Alim Qasimov; and with the heart-stopping sound of the Mongolian diva Khongorzul Ganbataar, this travelling show raises the rafters wherever it goes.

There's no doubt about the benign effect that this may have on Asian music - particularly since the AKTC is also sponsoring music-schools - but the fact that Yo-Yo Ma's commissions are now being published as sheet-music raises a big question: do you not kill an oral tradition when you write it down? 'Yes!' shouts the Silk Road Project's Indian composer Sandeep Das. 'When the American players asked me for a score, I told them, no, write it on your heart.' But Yo-Yo Ma takes a different view. 'Notation is only one part of it. As Isaac Stern used to say, music is about what happens between the notes. When I play Bach, am I looking at the notes in front of me, when I've known them since I was four years old? Of course not!'

So, we should jettison that notion of an East-West musical divide, since both ends of the spectrum are pursuing the same goal. And consider instead the balance of needs: Asian musicians need the West's material support; Western musicians need spiritual sustenance from the East. The Silk Road Project is resplendently fulfilling both sides of that equation.

Michael Church's weekly reports on the Silk Road Project begin on 17 June in the BBC World Service's 'Music Review'

Yo-Yo Ma's latest album 'Obrigado Brasil' (Sony); Wu Man's 'Pipa: From a Distance' (Naxos World 76037-2); and Kayhan Kalhor's 'Ghazal: The Rain' (ECM 1840 066627-2) are all released this month. The ensemble's commissioned works are on 'Silk Road Journeys: When Strangers Meet' (Sony SK 89782)

- 3910 reads

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.